Yijie Zou (Anthropology – College of William & Mary)

Yijie Zou reviews director Shayan Momin’s short work, Hengdian Dreams, streaming in our NYU Culture & Media Program at 30 Years sessions.

Hengdian Dreaming attends to rural migrant workers who live in Hengdian, Zhejiang, China, the world’s biggest movie studio city. Multiple forms of media-related work take place in Hengdian: big real-estate tycoon investing in movie production, local governor promoting film-related tourism, state promoting nationhood on TV, and rural lumpen migrants worker seeking jobs of extra actor in historical drama while earning money by live streaming Hengdian life on digital platforms like Huoshan and Douyin (Tiktok). For these migrant workers, also known as hengpiao (Hengdian drifters), livestreaming for money in a production center for historical drama creates new media worlds that allow them to remake their relationship to labor. One key contrast that allows them to make this distinction is their experiences in other jobs related to export-manufacturing industries that have stimulated growth in China over the last forty years. Though all the protagonists in the documentary come from a rural background, and most of them have previous experience of working in these industries, I describe them as “migrant workers” in this review with hesitation. As the documentary unfolds, the feeling of hesitation grows stronger.

This hesitation might be a product of my years-long conversation about labor in China with Momin and our agreement with Marxist perspectives of political-economic trends in China, which see the decline of industrial profitability and overcapacity of the manufacturing sector turning many migrants superfluous to waged labor. But while many migrants in Hengdian could be described as labor becoming redundant to industrial production, the documentary does not represent hengpiao in such a convoluted way. The film carries out a very basic ethnographic task, simply asking people what they want in Hengdian. In Hengdian, the people who self-identify as hengpiao pursue a life that is hard to be comprehend by many seminal accounts of “Chinese migrant workers” which often emphasize exploitative wage-labor relationships and rural-urban differentiations. To be sure, this is not to say that those academic accounts are false. Social stratification remains a serious problem in China, as migrants are often caught between inequalities in the distribution of social welfare and a type of double-bind accumulation resulting from the commodification of land and labor (See Chuang 2015). However, as shown in the documentary, hengpiao do not necessarily understand their lives in the same way as other groups of migrant workers studied by social scientists.

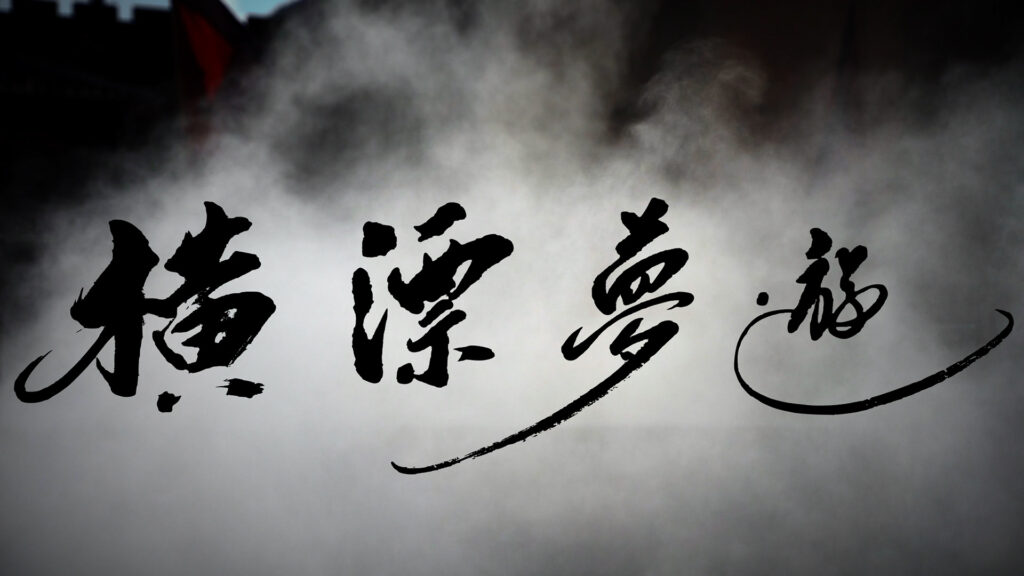

In Hengdian, the notion of “dream,” rather than an underprivileged state of exploited rurality, is the category deployed by migrants to understand the value of working in Hengdian. That is, the dream about becoming an actor while promoting oneself on live stream platforms is both a motivation and outcome for what these migrant workers consider as productive activities now, as compared with ideas about labor productivity defined by labor regimes in other sectors of the economy. Paradoxically, Hengdian life offers unemployed migrants a place for self-realization of individual value as well as a place to earn money (20:56). Achieving both of these goals at the same time seems to be a major problem for hengpiao. The most prominent case of contradiction in the film is the calligraphy-double Wang He. As a self-trained folk artist,Wang is hired as a hand-double to write calligraphy in historical dramas for leading actors. In the opening minutes of the film, Wang appears almost like an outsider of Hengdian who casts judgement on migrants in Hengdian. It is precisely because of his judgement he inserted the Chinese character for dream (梦 meng)in the poster shown in the opening scenes to differentiate himself from other hengpiao who he thinks are just lazy and lack dreams. (02:37). Like many people whose talent remains unrecognized by society (怀才不遇)[i], Wang constantly looks for the actualization of his value by practicing calligraphy in Hengdian. But he also believes that efforts and time he invests in building up calligraphic craftsmanship cannot be reduced to several hours of remunerative live-streaming work, bemoaning that his time practicing calligraphy is worth more than a bowl of noodles .After repeated interventions from Zhang Xiaoming—the owner of the Good Luck Photo Studio who shares screen time with Wang He, who show Wang some reasonable calculations about the potential monetary value of live streaming, the same Wang He decides to live stream his calligraphic works online, ending up joining the evening crowds of live streamers on the square, with the scroll about Hengdian drifter’s dream in hands. Though it is unknown whether Wang keeps on live streaming afterwards, his mental journey shows how real Hengdian dream is for drifters in their attempts to find socially validated ways of economic and cultural self-realization.

As one can see in several scenes in the documentary, people live by performing what would have been otherwise considered peculiar behavior in other places. One hengpiao states this explicitly: in another city, the pressures of your job might make you feel like ranting to yourself on the street, and others might think you’ve lost your mind. But not in Hengdian. In Hengdian, a mirror city – by borrowing the concept from Dai Jinhua – where social relations are mediated through different cross-referencing visual representations in media, dream appears to be a theme that binds different activities together. For example, the film hints at the importance of historical drama in the Chinese Communist Party’s (CCP) view of their historical mandate. ( 03:44) is in view in the town. To facilitate the production of historical dramas as the CCP became more invested in representations of Chinese history, Hengdian Group built replicas of ancient Chinese megastructure for various historical dramas, for instance, the Qin Emperor Palace in Zhang Yimou’s Hero (09:32). Indeed, replica architectures in Hengdian recently appeared in CCTV’s documentary General History of China, the narrative of which reflects the state’s attempt to rejuvenate the China dream, a project Chinese New Left scholars describe as a synthesis of the multi-ethnic Chinese nationhood, the political community of China, and the great historical continuity under the party state (tongsantong). But this view also informs the desires of Old Jiao, a long-time hengpiao who wants to direct a drama in Hengdian and has a dream of the future synthesis of Chinese civilization and world peace that is more ambitious than the CCP (23:28).

In other words, hengpiao make their own dreams, but they do not make them as they please. The repeated invocations of dreams in the film reminds me of anthropological research the Dreaming’s role in mediating cosmological orientations, social belonging, and ideas about productive activity among indigenous groups in Australia (Munn 1970; Myers 1990). The Dreaming is not just a series of stories or (as a neuroscientist might say) a pattern of neurological electric flow in the brain. Dreaming mediates a series of transformations between cosmological entities and their material forms, a social activity that requires and leads to the reproduction of social relations. The Dreaming guides people’s actions and binds them together as they create what they perceive as a productive reality in day-to-day life.

While there are clear limits to linking concepts derived from ethnographic studies of Australia to China’s high capitalism in the twenty-first century in an ahistorical fashion, the insight about the reification of dreams offers a departing point to rethink the argument made by Pun Ngai in her classic ethnography about Chinese factory workers (Pun 2005). In that book, Pun had already adopted the dream as a sociological fact to explore the inspiration of becoming a modern worker. Motivated by these dreams, Chinese migrant workers in the 1990s participated in the (re)production of global capital, a process that in turn transformed material forms as well as ideas about a desirable life within proletarianized cultural worlds. The Hengdian dream also shares with the factory dream the same interests in work, labor time, monetary mediation of social relations, and self-expanding accumulation of profit, some basic categories of capitalistic value production that create the material world we live in.

But there is a difference. In Pun’s interpretation, the dream still belongs to the realm of social reproduction: it is an aspirational avenue for migrants to find a way out from the old family ties and, at times, from the exploitative wage-labor relationship in factories. In other words, Pun’s factory workers are motivated by a dream. In Hengdian, for rural migrants who are surplus to industrial production, dream is not just an idea to live by but itself a form of remunerative media work in China’s emerging digitized economy. In a sense, the cultural-economic dynamic within Hengdian dream of acting and live streaming inverses the popular Chinese saying that “One cannot live on dreams alone” (mengxiang buneng dang fanchi 梦想不能当饭吃).

The question about the future of migrant workers in China is not only of academic significance but also of political and economic importance. Admittedly, Hengdian Dreaming does not offer a clear answer to this question. It also does not give much information about how to understand the social organization or class position of Hengdian drifters, which are crucial for understanding the overall standing of the surplus population. But it is unfair to place this heavy duty on one documentary focusing on the media worlds of unemployed migrant workers. After all, class position, in many cases, only become explicitly formed in moments of political struggle or generalized economic turmoil, and both are absent in the film. What Hengdian Dreaming does —by virtue of its ethnographic approach — is to successfully give a new view on the meaning of digital platforms among migrant workers. The dream in Hengdian, enabled by the digital economy, is not delusional and fake, as drifters live on the dream by participating in remunerative works of live streaming. The ways in which hengpiao organize the activities of live streaming and acting in relation to the practices of self-valuation indicate that Hengdian dream cannot be simply understood in terms of alienation and exploitation that characterizes the 1990s’ “living-by-the-dream” life in factory shop floors. The film shows platforms are also not necessarily a cultural space of resistance in which rural migrant workers challenge their underprivileged state under rural-urban division. These are all important for understanding the historical transition of the figure of rural migrants within capitalist social relations in China, a topic that concerns scholars of modern China. Beyond this, the documentary also offers some ethnographic portal and empirical ground for further reflecting about the relationship between digital technology and work under capitalism. Having a look at this issue is timely in an era when a livestreaming platforms owned by a Chinese company plays a central role in the new Cold War between a “job-losing” America and the “technology-thief” China, and in a time when the culture of overwork prevalent in China’s booming digital industry becomes a trigger of social grievance among young office workers

You can watch Shayan Momin’s short work, Hengdian Dreams, streaming in our NYU Culture & Media Program at 30 Years sessions.

Reference:

Chuang, Julia. 2015. “Urbanization Through Dispossession: Survival and Stratification in China’s New Townships.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (2): 275-294.

Dai, Jinhua 戴锦华.1995. Jingcheng tuwei: nvxing dianying wenxue 镜城突围: 女性・电影・文学 [Breaking out of the Mirror City: Female, Cinema, and Literature]. Beijing: Zuojia chubanshe.

Munn, Nancy D. 1970. “The Transformations of Subjects into Objects in Walbiri and Pitjantjatjara Myth.” in Australian Aboriginal Anthropology: Modern Studies in the Social Anthropology of the Australian Aborigines, edited by Ronald Berndt, 141-163. Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies & University of Western Australia Press.

Myers, Fred. [1990] 2016 “Burning the Truck and Holding the Country: Pintupi Forms of Property and Identity.” HAU: Journal of Ethnographic Theory 6, no. 1 (June 1, 2016): 553–75.

Pun, Ngai. 2005. Made in China: Women Factory Workers in a Global Workplace. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

[i] For more details about calligraphic as a bodily skill constitutive of a type of Chinese masculinity associated with literary-art-based authority, see Angela Zito’s ethnographic film Writing in Water, which shows how retirees in Beijing—whose lives were previously organized through the socialist danwei (work-unit) system—spend their newfound free time in public parks practicing water calligraphy and creating communities of self-cultivation.