Two “sensory ethnographies” drew us into the darkness at this year’s RAI Film Festival. Festival Reporter Ozy Coombes-Cowell spoke to the directors of NIISHII丨Night Worlds and Guardians of the Night to trace the techniques that underpin these sensuous engagements with nocturnal life.

we wanted to think about the night from a sensorial perspective – and not primarily through our eyes – we wanted to sense darkness, breeze, smell, and more specifically the sounds that are so present when our eyes can’t see very well.

Alexandrine Boudreault-Fournier and Eleonora Diamanti

Directors, Guardians of the Night

a very important responsibility and challenge of visual anthropology, other than creating a sensory experience beyond what can be encapsulated in a text, is to engage wider audiences.

Saranya Nayak

Director, NIISHII丨Night Worlds

After the founding of The Harvard Sensory Ethnography Lab in 2006, interest in “sensory ethnography” has boomed. Films like Leviathan (Verena Paravel, Lucien Castaing-Taylor, 2013) have had a particularly high profile. But the practices of sensory ethnography are still evolving, and the field is shifting. Definitions are up for grabs. In short, we could say that sensory ethnography concerns itself with the embodied, multi-sensory experience of a given setting and those that inhabit it. On one level, films made in this mode can provide a pleasingly vivid impression of the sensations that a community habitually feel. But the form can also – at its best – illuminate the productive nature of the sensoria, and the social values and meanings associated with them.

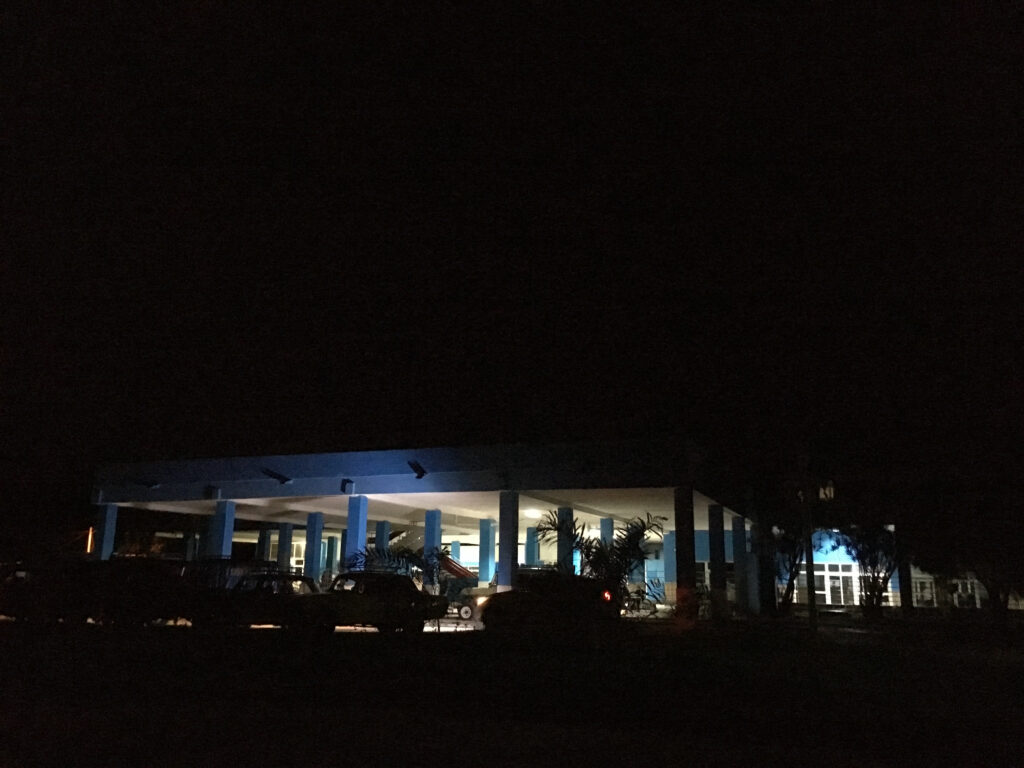

Much is to be learned from close examination of films that claim the label of “sensory ethnography”. This year’s RAI Film Festival showcases two new entries into the sensory ethnography canon: NIISHII│Night Worlds (Saranya Nayak / UK / 22 mins) and Guardians of the Night (Alexandrine Boudreault-Fournier, Eleonora Diamanti / Cuba, Canada / 17 mins). Each film takes us on an evocative tour of the night-time hours; NIISHII through the town of Dubrajpur (West Bengal, India), Guardians through Guantánamo, Cuba. Both utilise a range of affective methods to communicate the ‘feel’ of the night (from trance-inducing drums, to moist rice eaten with fingers), whilst also investigating what the feelings mean and do, as well as the prominence and significance of the different senses in different cultural contexts.

So, how do these sensory ethnographies work?

Both films take inspiration from Robert Gardner’s Forest of Bliss (1986), a renowned work of visual anthropology that explores India’s most holy city, Banares, in which the funeral industry is the main occupation. Gardner eschews voiceover and subtitles, in favour of an intricate, sensual montage of the everyday acts of craftsmanship that the deeply spiritual funeral ceremonies entail. Whilst the film seems to document roughly 24 hours, it was in fact shot over a few weeks, then edited to resemble a single day, from one sunrise to the next. Both Guardians and NIISHII were assembled in a similar fashion; shot over numerous nights, then later cut in such a way that suggests a journey that progresses over a single night, ending at dawn.

Furthermore – although NIISHII does include some scenes with subtitled dialogue – a great deal of both films involve wordless observational shots of townsfolk engaging in physical tasks. As such, we are invited to fixate on these activities, to contemplate the significance of an action or sensation – be it professional, recreational, personal, social, or spiritual. Take, for instance, a sequence in Guardians in which a ballerina stretches by tying her ankle to a railing above her head. The film invites us to ask: what does this represent? The way this body can be moved, shaped, and bound? And pain and discomfort endured? Well, this striking sequence alerts us to the presence of “body techniques” (as Marcel Mauss called the repertoire of embodied skills and knowledge) which we might not expect to encounter here. It draws attention to the diversity of contemporary Cuban dance culture – bodies don’t just move to salsa or reggaetón music in Cuba, the filmmakers show us. We see the ballerina use her smartphone as she exercises. Again, we ponder the sensuous world this girl inhabits. Earlier we saw words being penned into a notebook; the behaviour of this Cuban ballerina exemplifies a global shift where, increasingly, we communicate not by putting pen to paper, but rather through sliding fingers across the glassy texture of a glowing phone screen.

In lieu of dialogue, the audio of each film features a wealth of keenly recorded diegetic sounds. These soundtracks serve to create nuanced impressions of place, and encourage us to appreciate the far reaching ways that sound may be used to contextualise and enliven images (microphones, of course, are generally not subject to the same directional limits as cameras).

In both cases, the vibrant – or sometimes very still – off-screen spaces that surround the images are communicated through prevalent ambient noises. The faint buzz of electric lights and surrounding insects, the hubbub of busy spaces, and the rumbles, honks and screeches of passing traffic all contribute massively to the immersive atmospheres that the films cultivate. As the directors of Guardians emphasise, the film ‘needs to be listened at… The audience really needs to pay attention to the soundtrack first to fully appreciate the experience of the film’.

The opening images of both NIISHII and Guardians are accompanied by sudden, loud noises that prime the ears for the detailed soundscapes that follow. In NIISHII, a time lapse of nightfall is set the sound of a ‘Shankha’ being blown, a type of conch shell which, as Nayak tells me, ‘during the evening ritual has associations with victory, auspiciousness, warding off evil, beginnings and endings.’ Guardians, on the other hand, opens with a close up of the rotating gears of a bicycle, accompanied by the sound of a squealing mechanical brake, a noise which the filmmakers classify as ‘dark and metallic, even cold, a little bit like the ambience / atmosphere of the film itself.’ In addition, they note how this opening introduces a pattern of ‘the continuous and cyclic aspect of nocturnal rhythms. Rhythms that repeat endlessly, in a 24 hour cycle, similar but never exactly the same.’

These openings begin to indicate some formal differences that emerge between the two films. Guardians often toys with diegetic sounds, subtly blending and reorganising noises from different locations, and a sparse keyboard score frequently surfaces to complement the rhythmic and tonal progression of the piece. The filmmakers credit Guantánamo based composer Zevil Strix for ‘the poetic aspect of the soundtrack’, remarking once again on ‘cyclic rhythms’, and explaining that ‘environmental sounds blend with electronic compositions creating an estranging effect on the audience’. (Notably, two other Guantánamo based artists contributed to the film; choreographer Yoel Gonzalez Rodriguez served as producer, and graphic designer Joel Aguilar Fuentes produced the poster. The directors wish to emphasise that ‘the collaboration with local artists was essential for our project’.)

The lyricism of Guardians’ soundtrack – which was composed before the footage was edited – is reflected in the imagery. Largely, the film is a rich montage of tight close-ups, and shots from different scenes are often inter-cut based on thematic, graphic or sensory connections rather than on physical or temporal proximity. Take, for example, a sequence in which one woman having her nails filed and carefully painted by another is interspersed with shots of a mother and daughter curled up together in a ‘small and cramped, but also very tidy and clean’ home, ‘sharing that tiny space in a very loving and intimate way’.

The directors describe the close-up aesthetic as ‘very intimate and focused’, whilst highlighting that ‘there is a lot that is left outside – out of the frame, that we don’t know is there – and that speaks to the anthropological project in general.’ Recurrent lens flares and shifts in and out of focus afford the film a delicate visual splendour, whilst also creating an impression of the glare of bright electric lights at night, and a feeling of seeing through bleary, fatigued eyes. Both of these techniques impair vision, encouraging greater reliance on the ‘alertness of other senses, especially hearing’.

Although Nayak acknowledges a ‘definite inclination towards creating a mood, ambience or affect’, she characterises NIISHII as ‘more observational than poetic’. Having initially considered setting her film in one of two mega-cities where she’d lived – Delhi or Kolkata – Nayak opted to locate the fieldwork in the small town Dubrajpur because it ‘offered a chance to explore a landscape in transition, a semi-urban space in between a village and a city’. She explains that this ‘presented an opportunity to trace the evolution and co-existence of lightscapes and soundscapes at night while traces of the past still lingered in occasional practice and in popular memory’. Throughout the film, close ups of warmly glowing lanterns and candles are juxtaposed with shots of cool, fluorescent, electric light sources. Nayak reports that ‘the lighting of different kinds of lamps representing dying lightscapes in an increasingly electrically powered world were easily the most compelling images for me’.

NIISHII incorporates various passages of dialogue that offer interesting suggestions of the ways that light and sight figure into the locals’ lives. Reports range from the difficulty of affording electricity, to a rumoured ‘light ghost’ which concerned people enough that they used rags to seal the cracks in their doors at night, to a couple discussing the judgement that women face if leaving the house alone, to a woozy father explaining that, ‘in drinking dens, darkness is best’. These and other verbal vignettes paint an intriguing picture of the town’s attitudes to exposure. Nayak observes that ‘the fieldwork points to the presence of a common desire to control the light and visibility around oneself. However, the power dynamics around this control have shifted dramatically with the explosion of state sponsored electrically powered sources lighting up more and more spaces as days go by’. And on the topic of ghosts, she had this to say: ‘Everyone I met in the town had a ghost story to tell, and many were eyewitnesses or had experienced some kind of ghostly presence in person. Higher visibility and brighter nights as a result of urbanisation has drastically reduced such experiences, which in my opinion is a fundamental change to how people see what they are able to see at night.’

Guardians of the Night and NIISHII丨Night Worlds each employ a variety of techniques to create potent multi-modal perceptions of the towns which they explore. By striving to engage the whole sensoria – via detailed sound design as much as through visual material – the films offer absorbing and memorable tours of the night-time hours in their respective towns. Through carefully considered cinematography and editing, and in the case of NIISHII, verbal testimonies, the filmmakers reveal interesting aspects of the relationships that various demographics have to the senses in different cultural contexts. Just as the films shift perspectives away from the dominance of the visual in present culture by examining the darker side of our 24 hour life cycle, so too do they illuminate the fact that ever growing electrification is resulting in the increasing encroachment of the visual on night-time life in urban environments. Both films are intricate, accomplished contributions to the field of sensory ethnography, and valuable case studies of practices that may be employed when working at this exciting frontier of ethnographic film.